|

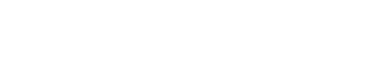

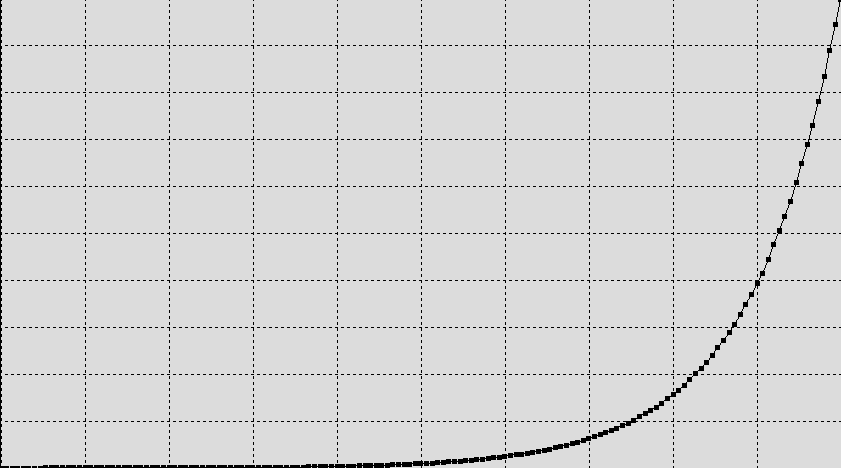

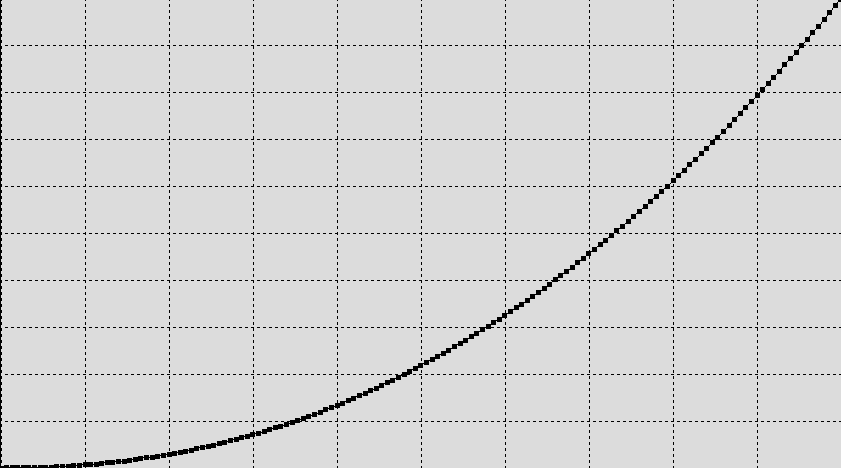

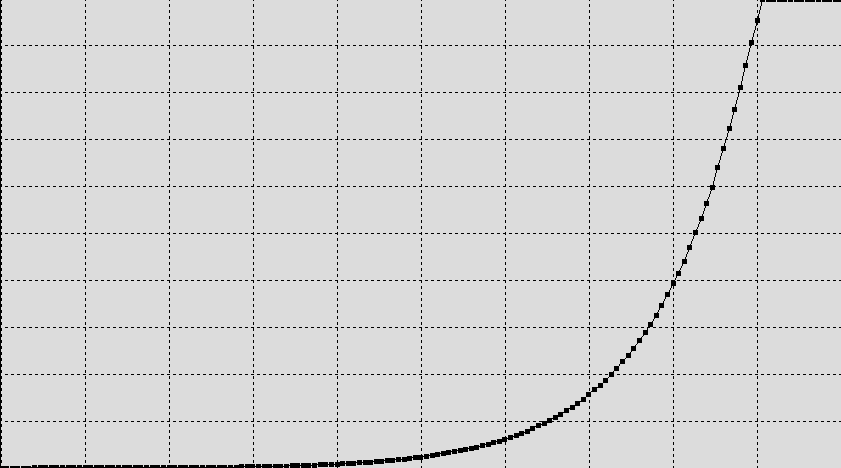

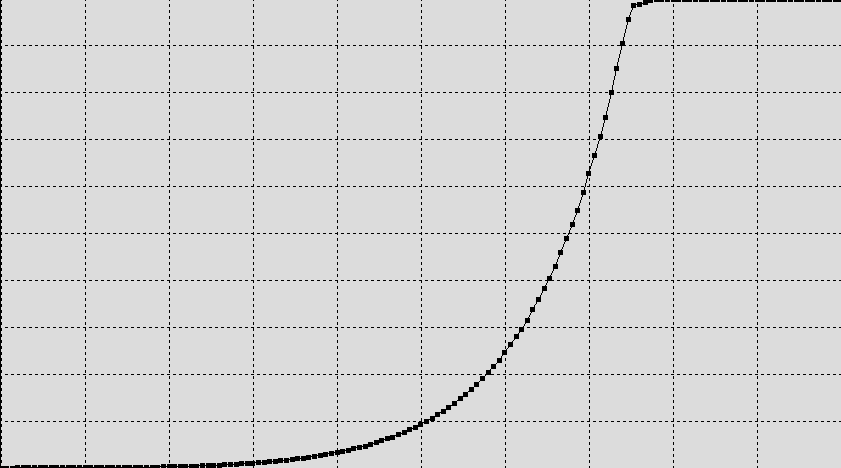

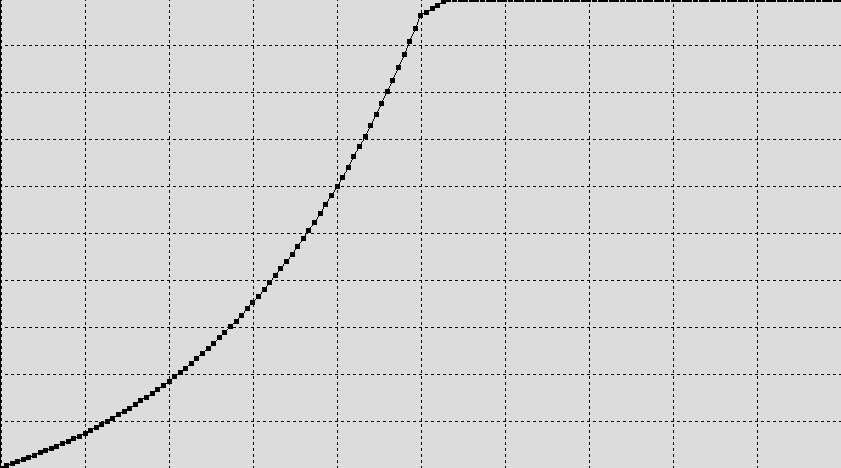

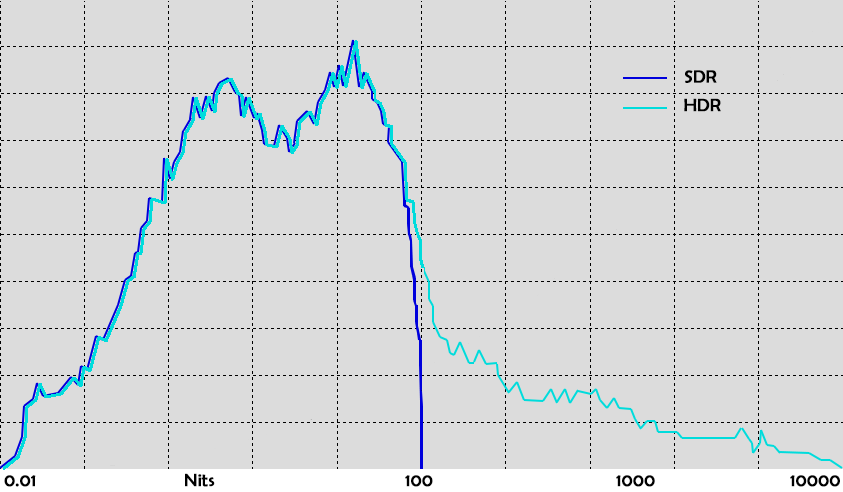

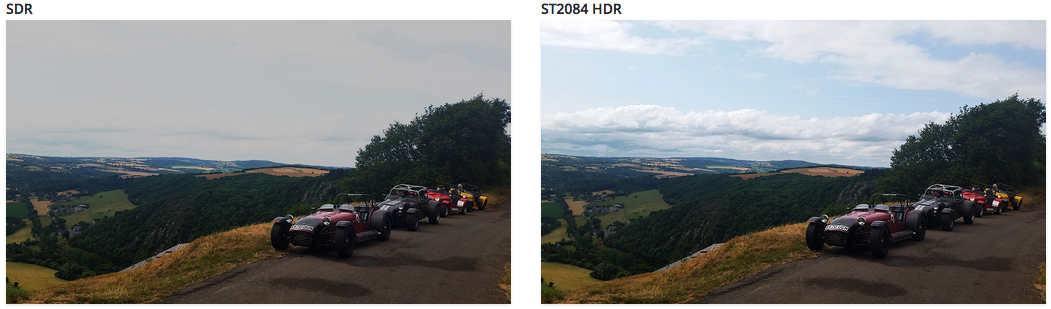

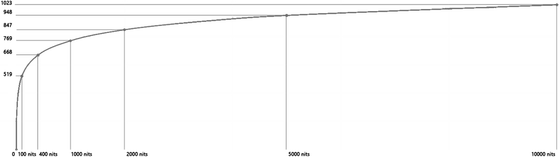

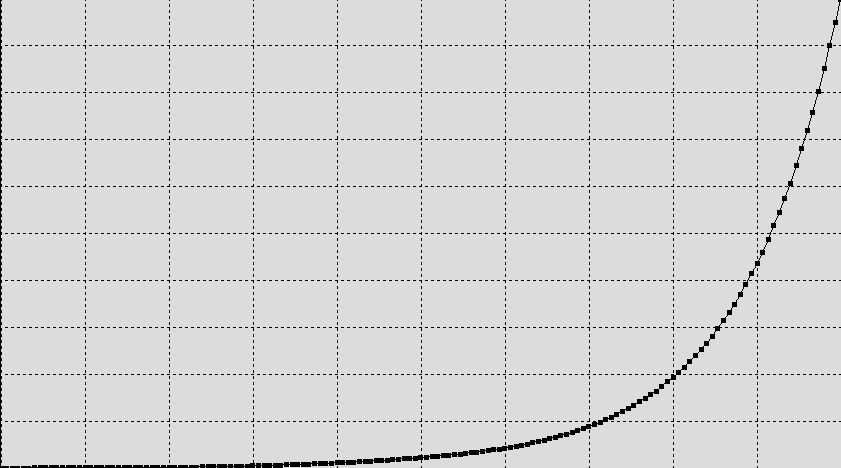

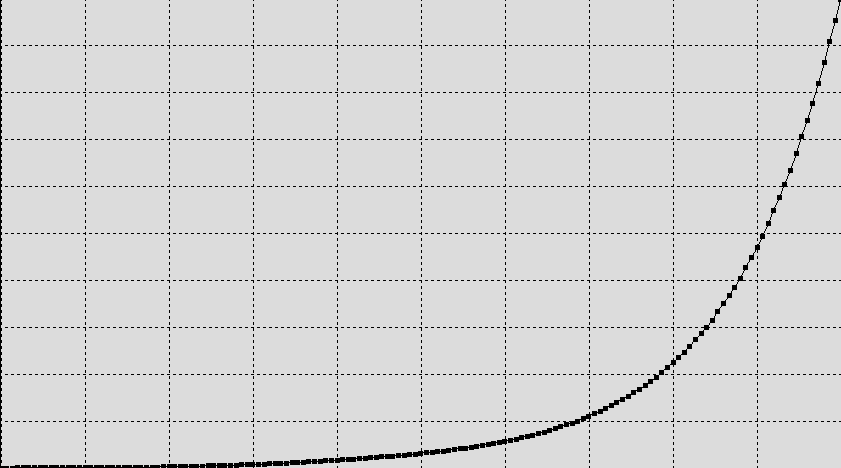

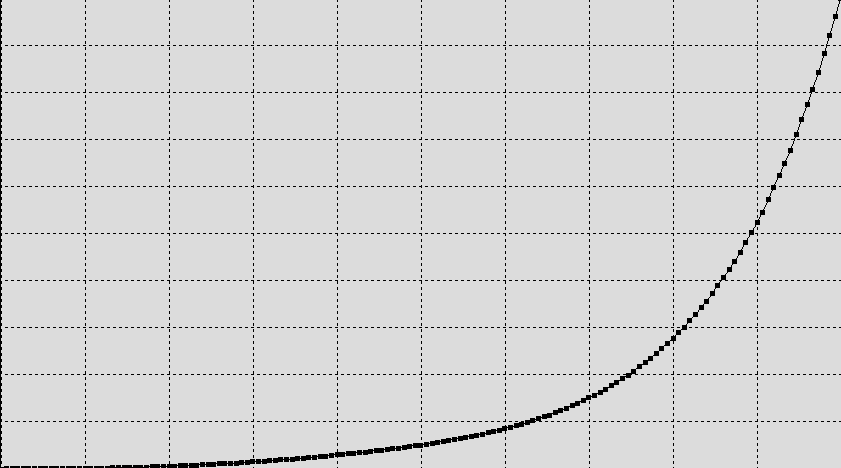

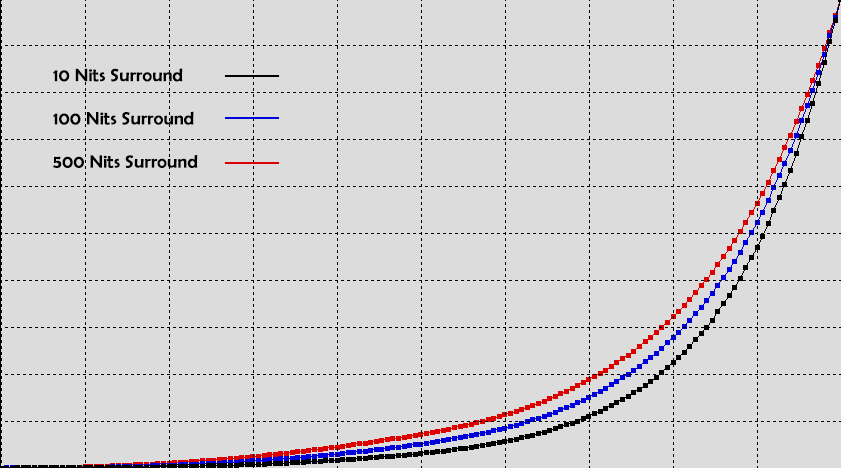

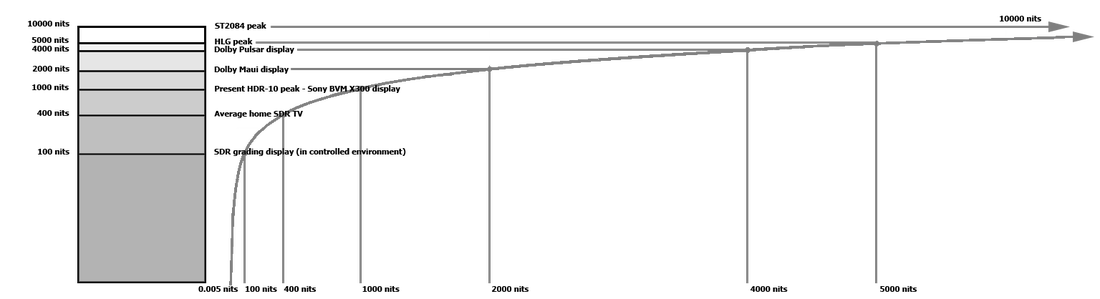

written by Steve Shaw from Light Illusion Understanding UHDTV Displays with HDR, LLG, and WCG. UHDTV, combining HDR (High Dynamic Range) or HLG (Hybrid Log-Gamma) with WCG (Wide Colour Gamut) imagery is gaining momentum as the next enhancement to our viewing experience. However, the whole UHDTV concept, using HDR/HLG/WCG is as yet very undefined, and even the basics can be very difficult to get to grips with. UHDTV UHDTV (Ultra High Definition TV) has had something of a difficult birth, with different display manufacturers effectively defining their own 'Ultra HD' specifications. In response, the UHD Alliance has released a definitive (for now) Ultra HD specification, linking together all the display parameters required to be accepted as UHDTV, although the individual aspects of the UHDTV specification can, and often are, used in isolation. There is nothing to stop a standard gamut display (Rec709), with standard HD or even SD resolution, working with HDR/HLG contrast, for example. To read more regarding the UHD Alliance, and their specifications, see: www.uhdalliance.org. Within this tech page we are focusing specifically on HDR/HLG, and WCG, and what they mean for display calibration, image workflows and the end image viewing experience. HDR & HLG HDR and HLG are not just about brighter displays, they about using the greater available display brightness to enable extended detail within the brighter highlights. As such, the gamma curve needs to be set differently for displays with different peak brightness levels, and for different HDR standards, such as SMPTE's ST2084 (as used with Dolby Vision ands HDR10) and the BBC's suggested WHP-283 Hybrid Log-Gamma (HLG) format. Note: It is also worth noting that Dolby Vision specifies 12 bit imagery, while HDR10 and HLG are 10 bit based. As a result, no 10 bit HDR/UHDTV material can be considered as being true Dolby Vision. ST2084 HDR ST2084 defines the EOTF (Gamma) for the Dolby Vision and HDR10 HDR formats. Within LightSpace the ST2084 HDR EOTF is available as a preset for Rec709, P3 and Rec2020 colour gamuts. ST2084 is based on a theoretical 'Golden Reference' display with 10,000 nits max luminance capability, with all 'real world' displays referenced to this theoretical display, and has a gamma curve (EOTF - Electro Optical Transfer Function) as follows. This shows that only a small portion of the image DR would use the extended brightness capability, with the majority of the image being held very low. (These are relative display gammas, not conversions from different image sources to different displays!) The ST2084 HDR specification "aims to define an EOTF that is intended to enable the creation of video images with an increased luminance range, not for the creation of video images with overall higher luminance levels". This means that reference white (normal diffuse white) remains at 100 nits, which is exactly the same as for SDR displays (Standard Dynamic Range). Above 100 nits are spectral highlights only. This shows that the Average Picture Level (APL) of a ST2084 HDR display will not be significantly different to a SDR display (see the Histogram diagram below) If you compare this to a standard Rec709 gamma curve the difference is obvious. However, different HDR displays have different peak brightness levels and therefore require modified gamma curves, such as for Dolby's 4000 nit Pulsar monitor, which requires a HDR gamma curve that peaks at around 90% of the ST2084 standard. And the following ST2084 HDR gamma curve shows by comparison what a 100 Nit monitor would display. ST2084 HDR - What does it really mean?The biggest confusion with regard to ST2084 HDR is that it is not attempting to make the whole image brighter, which unfortunately seems to be the way most people think of HDR, but aim to provide additional brightness headroom for spectral highlight detail - such as chrome reflections, sun illuminated clouds, fire, explosions, lamp bulb filaments, etc. ST2084 EOTF - What it really means for picture levels The following is taken directly from the ST2084 specification. This EOTF (ST2084) is intended to enable the creation of video images with an increased luminance range; not for creation of video images with overall higher luminance levels. For consistency of presentation across devices with different output brightness, average picture levels in content would likely remain similar to current luminance levels; i.e. mid-range scene exposures would produce currently expected luminance levels appropriate to video or cinema. The ST2084 HDR specification defines reference white (normal diffuse white) as being 100 nits, which is exactly the same as for SDR displays (Standard Dynamic Range). Above 100 nits is for spectral highlight detail only. This shows that the Average Picture Level (APL) of a ST2084 HDR display will not be significantly different to a SDR display. So the reality is that ST2084 HDR should just ADD to the existing brightness range of SDR displays, meaning that more detail can be seen in the brighter areas of the image, where existing displays simply clip, or at least roll-off, the image detail. The following histogram is a simplified view of the difference between a SDR (Standard Dynamic Range) image, and its ST2084 HDR equivalent. Note that the APL (Average Picture Level) remains approximately consistent between the SDR and ST2084 HDR images, with just the contrast range and specular highlight levels increasing. Note: It is worth noting that no matter what is said elsewhere, no HDR standard can produce 'darker blacks', as they are set by the min black level the display technology can attain, and the present day SDR (Standard Dynamic Range) Rec709 standard already uses the minimum black attainable on any given display. HDR - The Reality of Black The following statement is taken from Dolby's own 'Dolby Vision for the Home' white paper. "The current TV and Blu-ray standards limit maximum brightness to 100 nits and minimum brightness to 0.117 nits..." Unfortunately, at best this is an inaccurate statement, at worse it is marketing hyperbole, as the Blu-ray format has no such limits for min or max brightness levels, as these values are defined by the display's set-up. The minimum level (the black level) is usually just the minimum the display can attain, and can range from very dark (0.0001 nits for example) on OLED displays to higher levels (around 0.3 nits or even higher) on cheap LCD displays. The maximum brightness is often set far higher on home TVs to overcome surrounding room light levels, with many home TVs set to 300 nits, or more. Note: The statement that 'The minimum level (the black level) is usually just the minimum the display can attain' refers to the fact that often OLED black can be too low, and users often chose to lift it to prevent shadow detail clipping. When the original Blu-ray material is graded, the displays used will be calibrated to 80-120 nits (100 nits being the common average value), within a controlled grading environment (a dark environment), with the black level being from around 0.001-0.03 nits, depending on the display used (although the higher value is often used to maintain 'pleasant' images when viewed on the wider range of home TVs, with variable black levels!). And as mentioned above, when the Blu-ray is viewed in a home environment it is often necessary to set the TV to brighter levels to overcome surrounding room light levels. The reality is HDR does nothing for black levels - no matter what certain 'marketing material' may say. (Note: we are not discussing bit depth: we are discussing the relative image black levels. HDR's 12 bit or 10 bit vs. SDR's present 8 bit is a different discussion, and there is no reason SDR can't be 12 bit or 10 bit, and also gain the benefits that brings...) The following images simulate the comparison of an SDR image with its ST2084 HDR equivalent. (Obviously, as your display can not adjust its peak brightness this simulation is rather compromised! But, it does show the main body of the image remains consistent in brightness, with the extended dynamic range allowing additional detail to be seen in the highlights.) And if we 'normalise' the images, we can see the SDR/HDR difference in a more simplified way. Unfortunately, most ST2084 HDR demonstrations do not map the contrast range correctly, with the result that the overall image is simply much, much brighter, which is not the main intent of ST2084 HDR, as shown above. Obviously, in the real world the extra dynamic range available with HDR would be used to re-grade the image creatively to benefit from the additional dynamic range - but extended highlight detail is the true reality of ST2084 HDR. Different Displays & ST2084 HDRObviously, different HDR displays will have different peak luminance capabilities, and so the displayed image will need to clip to the peak nits value available, as defined by the above ST2084 EOTF graphs. This 'peak luma clip' is controlled by meta-data within the signal, defining the peak luma of the display used to perform grading, which is used by the presentation display to set the correct 'clip' level. How this clip is performed - a hard clip, as per the above EOTF curves - or a soft clip, with roll-off, has not been defined. The reality therefore, is that it is unlikely two displays will present the same image in the same way, even if they have the exact same peak nits capability, as the process used for peak luma clipping will not be identical. Peak Luminance & Bit LevelsAs the ST2084 standard is an absolute standard, not relative, each and every luminance level has an equivalent bit level. For a 10 bit signal the levels are as follows. The alternative HLG standard is a relative standard, so always uses the full bit levels. BBC HLG HDR Within LightSpace the BBC HLG HDR standard is available as a preset for Rec709, P3 and Rec2020 colour gamuts. Unlike ST2084, the BBC HLG HDR standard is not based on a reference display with a specified max luminance value; instead the standard changes the EOTF gamma curve based on any given display's actual peak Luma value, as well as the display's Surround illumination. The BBC HLG standard has a gamma curve (EOTF - Electro Optical Transfer Function) as follows, and again shows that only a small portion of the image DR would use the extended brightness capability, with the majority of the image being held relatively low. (Again, these are relative display gamma graphs, not conversions from different image sources to different displays!) The BBC HLG standard doesn't use a specified reference white point in nits, but instead places it at 0.5 (50%) of the peak luminance. The BBC HLG standard is designed for displays up to approximately 5,000 nits, so lower than the ST2084 standard's 10,000 nits, but with the reality of what peak brightness levels HDR displays will actually be capable of is more than enough. While the above HLG curve is for a 5000 nits display, the below curve is for a 1000 nits display. And the following curve is for a 100 nits display. All the above BBC HLG curves are based on a low 'Surround' illumination of 10 nits. It is this 'Surround' value that is important, as in addition to using the display's peak Luma value to calculate the EOTF, the BBC's HLG standard also uses the display's surround illumination to alter the system gamma, as shown below for a 1000 Nit display. Different Displays & HLG As the HLG format has no reliance on meta-data there is a far better level of likely image consistency across different displays. Additionally, the use of the display's surround illumination to alter the system gamma attempts to adjust display calibration to counter for differing viewing environments. A first real attempt to offer 'viewing consistency' across differing viewing environments. This is an area where ST2084 based HDR will struggle - see 'Viewing Environment Considerations' below. HDR - The Reality & Associated Issues The biggest issue with HDR displays is they can actually be painful to watch, due to what is often termed as excessive eye fatigue... The problem is the difference between the human eye's huge Dynamic Range, which has a dynamic contrast ratio of around 1,000,000:1, or about 24 stops. It is this dynamic adaptation that enables us to see detail in dark environments, as well as in bright sunlight. However, at any single given time the human visual system is only capable of operating at a fraction of this huge range. It is this static dynamic range, which occurs when the human visual system is in a state of full adaptation, and it is this that is active when watching home TV and some theatrical presentations at 'normal' viewing distances. While there are few exact figures for the human eye's static dynamic range, many agree it is around 10,000:1, for average viewing environments, which is around 12 Stops.

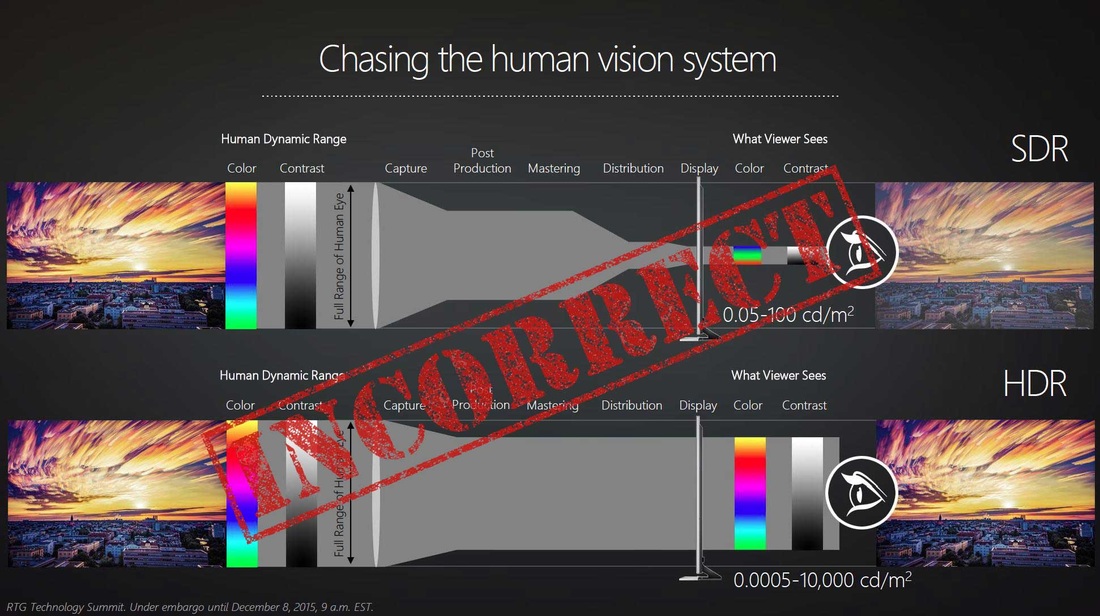

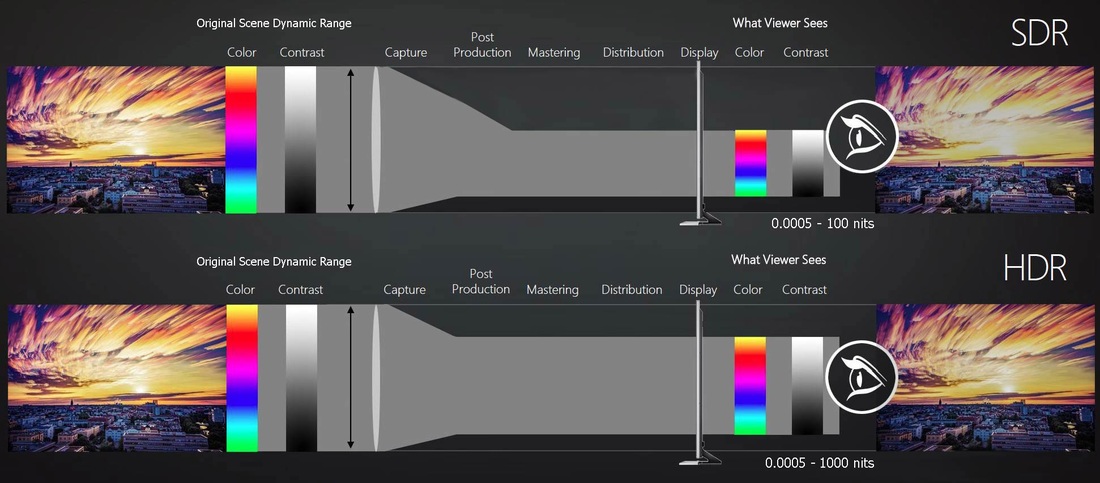

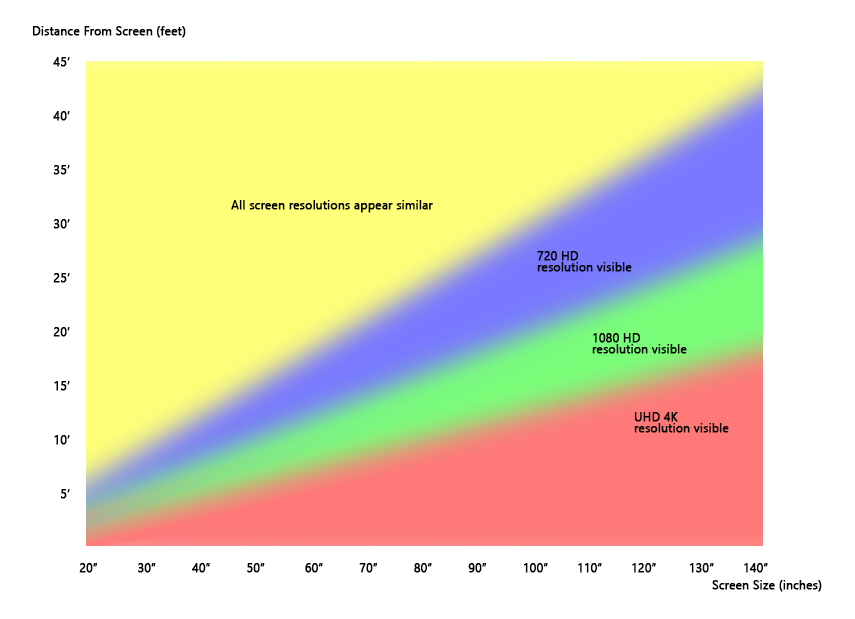

Do you really sit this close to your TV? What all this really means is a display with an excessive HDR will potentially cause real eye fatigue at normal viewing distances, and will very likely be be painful to watch. HDR - Incorrect Assumptions?An example of the way HDR is often portrayed is by using a diagram similar to the following, showing how the wide dynamic range of the real world is presently reduced to the limited dynamic range of SDR TV (Standard Dynamic Range TV), and how HDR will maintain more of the original scene range. The above image has been widely distributed on the internet, although it seems the image originated with an AMD presentation, and is used to show the assumed benefits of HDR vs. SDR. But, the image contains a number of errors and incorrect assumptions.

HDR - Black LevelsIt is worth reiterating again that no matter what is said elsewhere, no HDR standard can produce 'darker blacks', as they are set by the max black level the display technology can attain, and the present day SDR (Standard Dynamic Range) Rec709 standard already uses the minimum black attainable on any given display. In the reality of the real world, an excessive HDR display would be one with a peak brightness over around 650 to 1000 nits. (The darker the viewing environment the lower the peak value before eye fatigue occurs, which causes another issue for HDR - see 'Viewing Environment Considerations' below.) The Ultra HD Alliance seems to be aware of this, and actually has two different specifications for today's HDR displays:

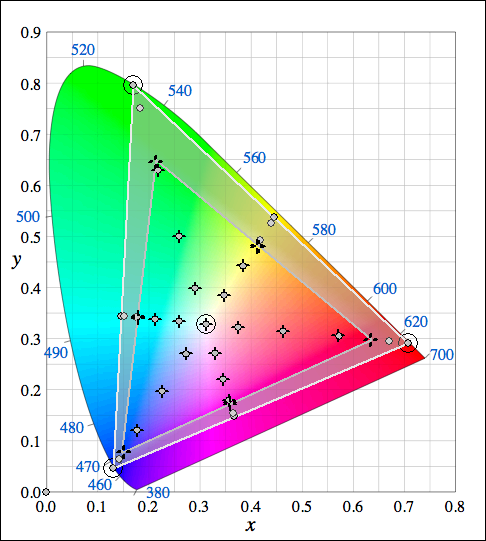

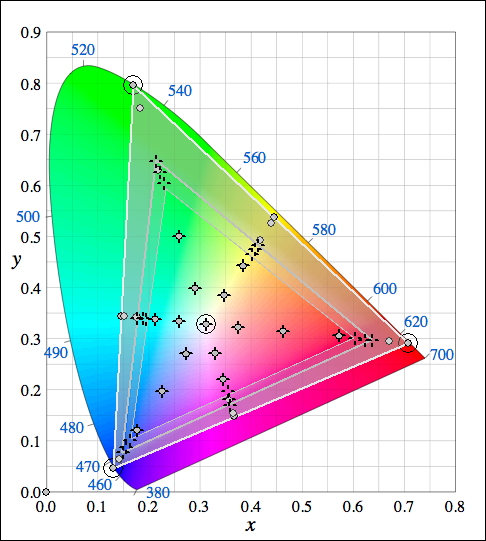

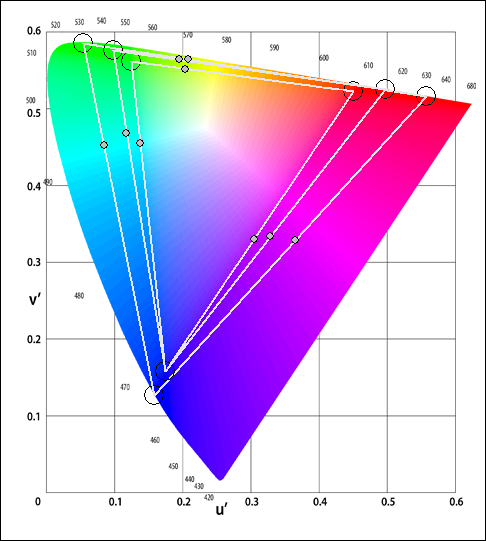

HDR - White LevelsIt is worth pointing out that due to the logarithmic response of the human eye to changes in light levels, the present day SDR (Standard Dynamic Range) Rec709 'standard' of 100 nits is actually around 50% of the peak HDR 10,000 nits level. (Note: 'standard' is in commas as Rec709 is a relative standard, and so scaling the peak luma levels to overcome environmental light issues is an acceptable approach, while HDR ST2084 is an absolute nits based standard, and so cannot be scaled) The following image shows the reality of this when referenced to different peak white levels. Brightness LimitingAnother of the often overlooked potential issues with HDR has to do with the need to limit the power requirement of the display, as obviously extreme brightness causes excessive power consumption. That in itself is a cause for concern, based both on the power costs, and potential environmental issues. Hopefully, both those can be overcome with more efficient display backlighting technologies. However, in an attempt to overcome extreme power requirements, all HDR displays use one form or another of ABL (Auto Brightness Limiting - called Power Limiting in HDR terminology). In very simple terms ABL reduces the power to the screen dependant on the percentage screen area that goes over a predetermined brightness level, so reducing the overall brightness of the scene. The ST2084/86 specifications define what is known as MaxCLL (Maximum Content Light Level) and MaxFALL (Maximum Frame-Average Light Level) which are intended to be part of the HDR mastering metadata, from which the viewing display will calculate how to show the image, limiting potentially high power requirements. Obviously, this causes the same image to be viewed differently on different displays, with different shots of the same scene, with different framing, to also be seen differently on the same display as the average picture brightness level will be different depending on the shot framing, potentially causing different power limiting to be applied by the display in an almost perceptually random way. Such variations cause serious issues with accurate display calibration and image playback. Viewing Environment ConsiderationsOne of the often overlooked potential issues with ST2084 based HDR for home viewing is that because the display's various brightness (backlight and contrast) controls are already maxed out on HDR TVs there is no way to increase the display's light output to overcome surrounding room light levels - as is often done with SDR home TVs to enable different configurations for Day/Night viewing. This is an issue as UHDTV/HDR as the ST2084 standard is intended to enable the creation of images with an increased spectral highlight range, not to generate images with overall higher luminance levels. As has been stated previously, this means that for most scenes the Average Picture Level (APL) of HDR material will match that of regular SDR (standard dynamic range) imagery. The result is that in less than ideal viewing environments, where the surrounding room brightness level is relatively high, the bulk of the HDR image will appear very dark, with shadow detail becoming very difficult to see, as the eye's constricted pupil will just not be able to discern shadow detail. To be able to view HDR imagery environmental light levels will have to be very carefully controlled. Far more so than for SDR viewing. WCG - Wide Colour GamutAs part of the evolving UHDTV standard, WCG is being combined with HDR to add greater differentiation from the existing HDTV standards, using the Rec2020 colour gamut as the target colour space. The problem is that no (realistically) commercially available display can achieve Rec2020, meaning different UHDTV displays will have to 'adjust' the displayed image gamut based on the actual gamut capabilities of the display. This is provided for by the use of embedded meta-data within the UHDTV signal (associated with HDR meta-data, mentioned above) defining the source image gamut, aiming to allow the display to 'intelligently' re-map to the available gamut of the display. The issue is that once again, and as with HDR meta-data and peak luma clipping, there is no set gamut re-mapping technique proposed. The result is that different displays will manage the required gamut re-mapping in different ways, generating differing end image results. The above image shows the issue with attempting to display a wide gamut on a display with a smaller gamut. In this instance the display has a gamut similar to, but not identical to, DCI-P3, which is the stated 'preference' for smallest gamut for UHDTV displays (the smaller internal gamut triangle), while the larger gamut triangle shows Rec2020. The display has been calibrated to Rec2020, within the constraints of its available gamut, as shown by the gamut sweep plots (the measured crosses match with the target circles). However, the de-saturated area outside the display's available gamut, and within Rec2020, shows colours that will not be displayed correctly, with any colour within this area being effectively pulled-back to the gamut edge of the display. Obviously, the wider the display's actual gamut capability the less the clipping, and the less the different gamut capability will be visible, especially as within the real world that are few colours that get anywhere near the edges of Rec2020 gamut. To reduce the hardness of gamut clipping, gamut re-mapping can be used to 'soften' the crossover from in-gamut, to out-of-gamut. In the above diagram, the area between the new, smaller inner triangle, and the actual display gamut triangle shows an area where the display calibration is 'rolled-off' to better preserve image colour detail, at the cost of colour inaccuracy, effectively compressing all the colours in the de-saturated area into the smaller area between the display's max gamut and the reduced gamut inner triangle. In reality, gamut re-mapping needs to be far more complex, taking into account the fact that human colour perception reacts differently to different colours, so the re-mapping really needs to take this into account. The problem is that the UHDTV specifications do not specify the gamut re-mapping to use. However, from this it can be seen that in the real world no two Ultra HD displays will ever look the same when displaying the same images... Additionally, the Ultra HD specification, while using Rec2020 as the target (envelope) colours space, actually specifies that any Ultra HD display only has to reach 90% of DCI-P3 to be accepted as a UHDTV display - and 90% of DCI-P3 is not not much larger than Rec709. The above CIEuv diagram (CIEuv has been used as it is more perceptually uniform than CIExy) shows the gamut difference between 100% DCI-P3 and Rec709, as well as showing Rec2020. As can be seen, 90% DCI-P3 is not much larger than Rec709... Colour PerceptionAnd to end, a question regarding colour perception, for those of you Home Cinema enthusiasts... You watch a new film release in the cinema, in digital projection, using a DCI-XYZ colour space envelope for projection, containing DCI-P3 imagery. You then purchase the same film on Bluray, and watch it on your Rec709/BT1886 calibrated Home Cinema environment. Do you perceive any loss in image colour fidelity, assuming the Bluray master has been generated correctly? The reality is there are few colours in the natural world that exist outside of the Rec709/BT1886 gamut. Colours that do exist outside Rec709/BT1886 gamut tend to be man-made colours, such as neon signs, and the like... UHD ResolutionAnother component of UHD is the increase in resolution to 4K (3840x2160). While at first glance such an increase in resolution would appear to be a real benefit of UHD, it actually brings with it the question of the benefits can be appreciated? Resolution vs. Viewing DistanceThe higher the resolution, the shorter the viewing distance needs to be from the screen. Conversely, the greater the viewing distance, the lower the actual display resolution can be for the same apparent image resolution/quality. What this means in very simple terms is that a 'large' 55" 4K UHD screen will require the viewer to sit no further than 4 feet from the screen to gain benefit over a 55" HD resolution screen... This is shown in the following Screen Size & Resolution vs. Viewing Distance chart. Thanks for reading!

The original article was posted here: http://www.lightillusion.com/uhdtv.html It was written by Steve Shaw from Light Illusion. For any and all your Calibration tools please head to AVProStore.com

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Third Party Reviews & Articles

SIX-G Generator

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

|

|

© Copyright 2015-2023

Home Contact Us About Us Careers Warranty 2222 E 52nd Street North, Suite 101, Sioux Falls SD 57104 +1 605-330-8491 [email protected] |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed